x86_64 instructions may have many different parts to them. The order in which the instruction parts are listed is not at all related to the order in which they appear in the instruction encoding; instead I list the parts in an order that is likely to be easiest to understand. x86_64 is a complex instruction set, so understanding the basics before the hard parts is absolutely vital.

2.1) Opcode

First and foremost is the instruction opcode. The opcode denotes the actual operation that is being requested of the CPU. Instructions will only have a single opcode each, and opcodes will generally be 1 byte in size, however an opcode can be up to 3 bytes long. Some simple examples are:

0x90 is the opcode for NOP, which performs no operation.0xF3 0x90 is the opcode for PAUSE, which optimizes spin loops.0x0F 0x05 is the opcode for SYSCALL, which performs a syscall.

Note that some instructions, such as MOV, have many different opcodes depending on what type of move you are wanting. This will be elaborated on more later.

2.2) Prefixes

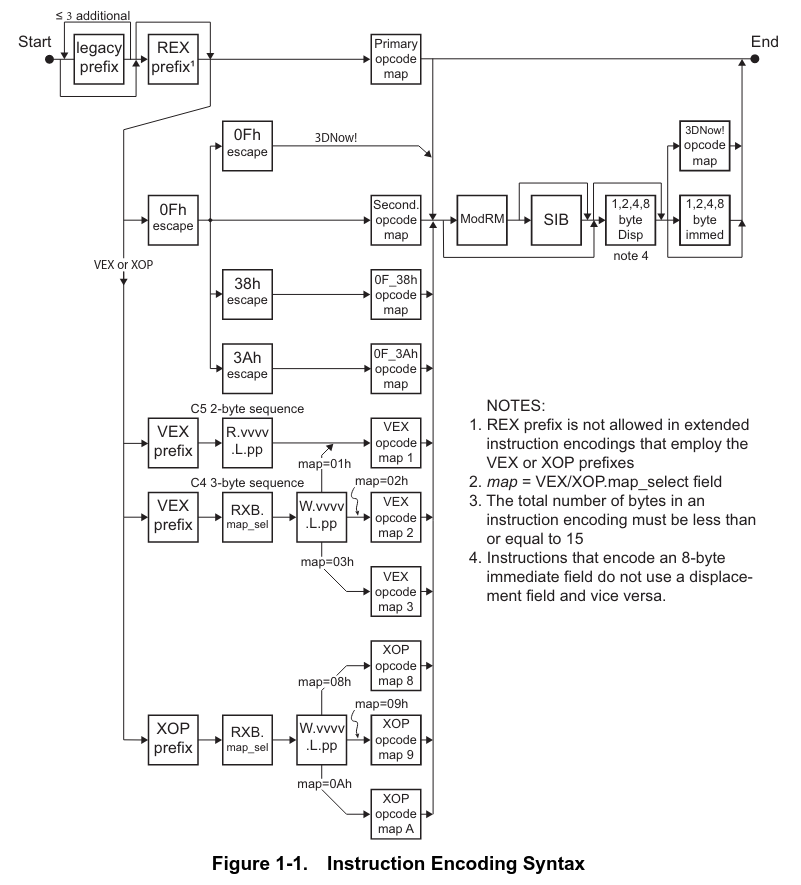

The next most important part of an instruction is its prefixes. Prefixes will often times modify many parts of an opcode, including changing the types of operands it takes, the sizes of operants, require additional bytes to be encoded into the instruction, etc. The so called "Legacy prefixes" are pretty simple, however the additional prefixes added in x86_64 (REX, VEX, XOP) are quite complex.

All legacy prefixes are 1 byte, as well as the REX prefix. The VEX and XOP may be either 2 or 3 bytes long. A single instruction can have up to 5 prefixes, 4 "legacy prefixes" and one additional REX, VEX, or XOP prefix. These prefixes are explained in further detail in the following sub chapters.

Another important explanation, code examples in this section may contain ----. This is simply imaginary spacing that I add to make bytes line up between different instructions, so the differences stand out more. For example:

0x01 0x02 0x03 0x04 0x06 Imaginary instruction 1

0x02 0x03 0x05 Imaginary Instruction 2

It is difficult to easily look at these 2 lines and easily tell which parts are the same and which parts are different.

0x01 0x02 0x03 0x04 ---- 0x06 Imaginary instruction 1

---- 0x02 0x03 ---- 0x05 ---- Imaginary Instruction 2

It is much eaiser to see the similarities and differences between the two.

2.2.1) Legacy - Operand-Size Override

This legacy prefix is denoted with the byte 0x66. In 64-bit mode, this prefix is used to tell an opcode that is being given 16-bit operands instead of the normal 32-bit operands. Unfortunately, the topic of operand sizing is complicated on x86_64, and there are different mechanisms for specifying different operand sizes. That means that this prefix is only used for this very specific case.

Here is an example of this prefix in action using a MOV opcode 0xB8:

---- 0xB8 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00 moves the four 0x00 bytes into the eax register.

0x66 0xB8 0x00 0x00 ---- ---- moves the two 0x00 bytes into the ax register.

2.2.2) Legacy - Address-Size Override

This legacy prefix is denoted with the byte 0x67. In 64-bit mode, this prefix is used to denote that a register holding a memory address id 32-bits rather than 64-bits. For example:

---- 0x8A 0x00 is a MOV instruction saying to dereference the memory address stored in rax and store the result in al.

0x67 0x8A 0x00 is a MOV instruction saying to dereference the memory address stored in eax and store the result in al.

I'm not sure how this would be useful in x86_64, and from what little I can find about this prefix, its use is discouraged.

2.2.3) Legacy - Segment-Override

There are a total of 6 different segments, each of which have a different prefix byte:

0x2E is the prefix byte for the CS segment0x3E is the prefix byte for the DS segment0x26 is the prefix byte for the ES segment0x64 is the prefix byte for the FS segment0x65 is the prefix byte for the GS segment0x36 is the prefix byte for the SS segment

There is actually a lot of misunderstanding about segments and 64-bit mode. According to the Linux kernel documentation, the FS segment is generally used for Thread Local Storage, and the GS segment is free for the application to use as it pleases.

The other 4 segments are not available in 64-bit mode unless a CPU feature called "Upper Address Ignore" is enabled. This CPU feature is documented in the The AMD64 Architecture Programmer's Manual Volume 2 Chapter 5 Section 10. It is not very likely that this CPU feature will be enabled unless you enable it yourself, so the CS, DS, ES, and SS segments will likely not be available in x86_64 unless you explicitly allow them.

Here is an example regarding the FS segment:

For the sake of the example, say that there is a variable named var that exists at memory address 0 relative to the FS segment.

---- 0x8B 0x04 0x25 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00 is the instruction that loads the memory address of var into eax.

0x64 0x8B 0x04 0x25 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00 is the instruction that loads the memory address of var relative to the FS segment into eax.

2.2.4) Legacy - Lock

This legacy prefix is denoted with the byte 0xF0. In 64-bit mode, this prefix is used to atomically change values in memory, which is important for lock-free algorithms. Note that because this prefix only modifies values in memory, it can only be used with instructions that operate on memory.

Here is an example of the lock prefix:

For the purposes of this example, iassume that RAX holds a memory address to a variable that is going to be incremented.

---- 0xFF 0x00 is the instruction that uses the INC opcode on the value pointed to by the memory address held in RAX.

0xF0 0xFF 0x00 is the instruction that atomically uses the INC opcode on the value pointed to by the memory address held in RAX.

2.2.5) Legacy - Repeat

This legacy prefix has 3 variants:

0xF3 is the prefix byte for REP, which repeats a string operation until RCX is 0.0xF3 is the also prefix byte for REPE/REPZ, which repeats a string operation until RCX is 0 or the zero flag is 0.0xF2 is the prefix byte for REPNE/REPNZ, which repeats a string operation until RCX is 0 or the zero flag is 1.

The REP prefix is used for string operations that involve some kind of memory copying, while the other prefixes are used for memory comparison instructions. An example:

---- 0xA4 is the instruction that uses the MOVSB opcode to copy a single byte from the memory address stored in RSI to the memory address stored in RDI, then increments RSI and RDI.

0xF3 0xA4 is the instruction that uses the MOVSB opcode to copy a single byte from the memory address stored in RSI to the memory address stored in RDI, then increments RSI and RDI. Bceause of the REP prefix, RCX is then decremented. This process is repeated until RCX becomes 0.

Another example with REPNE:

---- 0xA6 is the instruction that uses the CMPSB opcode to compare a single byte from the the memory addresses stored in RSI and RDI, then increments RSI and RDI, then sets the zero flag to 1 if the bytes are equal or 0 if not.

0xF2 0xA6 is the instruction that uses the CMPSB opcode to compare a single byte from the the memory addresses stored in RSI and RDI, then increments RSI and RDI, then sets the zero flag to 1 if the bytes are equal or 0 if not. Because of the REPNE prefix, RCX is then decremented. This operation repeats until RCX is 0 or the zero flag is 1.

2.2.6) REX

Based on many factors, I am thinking that the REX prefix is where most people throw their hands up and go "x86_64 is too hard, I give up", and this is for good reason! The REX prefix actually does many different things packaged together in a single instruction, and requires understanding a handful of things that have not yet been explained.

Because of the complexity and further prerequisite knowledge required to understand th REX prefix, we will actually go into it in much greater detail later. For now, jsut know that this prefix exists, and generally enables opcodes to work with 64-bit registers and values.

1.2.7) VEX and XOP

These prefixes are also quite complex, so these prefixes will also be documented later. Generally speaking, they are used for SIMD instructions, such as SSE and AVX.